1:38 pm

October 21, 2020

On the Oct. 8 episode of Inside Olympia, one of the guests was Speaker Laurie Jinkins. Host Austin Jenkins asked the speaker, “Republicans have said the worst possible thing you could do coming out of a recession is to raise taxes on people. What is the argument for considering sources of revenue, sources of taxation as part of the budget solution?”

Speaker Jinkins responded by saying that her first year in the Legislature was 2011, when budgets were still being cut in response to the Great Recession: “I experienced austerity budgets. And actually Republicans may say what they say but the actual research says that using an all cuts budget for the Great Recession actually hurt Washington’s recovery.”

Austerity budgets are those that reduce government deficits using spending cuts, tax increases, or both. Washington’s Great Recession response was not all cuts—it also included tax increases, fund transfers, reserves, and federal funds.

I’m not sure what research the speaker is referring to. I can’t find any that has answered how state budget cuts during the Great Recession affected Washington’s economic growth.

The general research on the economic effect of spending cuts is not cut and dried. In a 2001 paper, economists Peter Orszag and Joseph Stiglitz wrote that, in the short run, “economic analysis suggests that tax increases would not in general be more harmful to the economy than spending reductions.” But, as they note, the type of spending and the type of tax increase matters to the analysis.

On the other hand, economists Alberto Alesina, Carlo Favero, and Francesco Giavazzi have found (looking at austerity programs at the national level), “Tax-based plans lead to deep and prolonged recessions, lasting several years. Expenditure-based plans on average exhaust their very mild recessionary effect within two years after a plan is introduced.”

Of course, states face stronger budget constraints than the nation. Orszag and Stiglitz wrote,

It is worth emphasizing that any state spending reductions or tax increases are counterproductive at this time: they restrain the economy at a time when it is already slowing. Given the existence of balanced budget rules at the state level, some form of federal fiscal relief to states is therefore warranted.

Similarly, in 2016, Josh Bivens of the Economic Policy Institute asked why the recovery from the Great Recession was taking so long. He concluded that, because of the budget constraints faced by states, the blame lay with Congress.

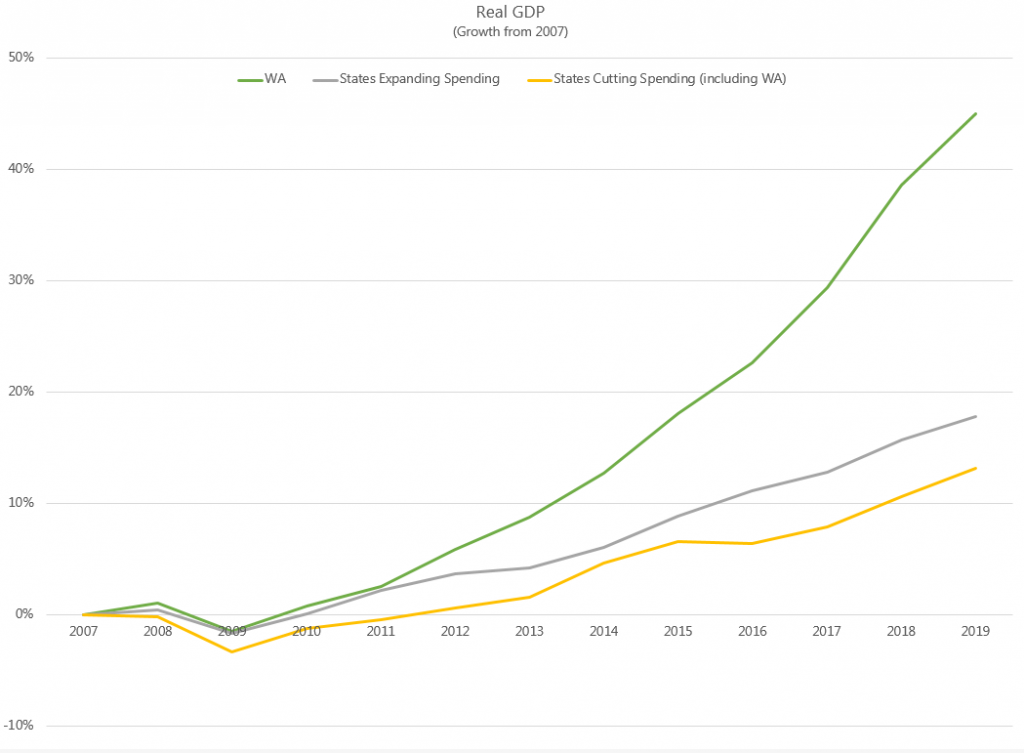

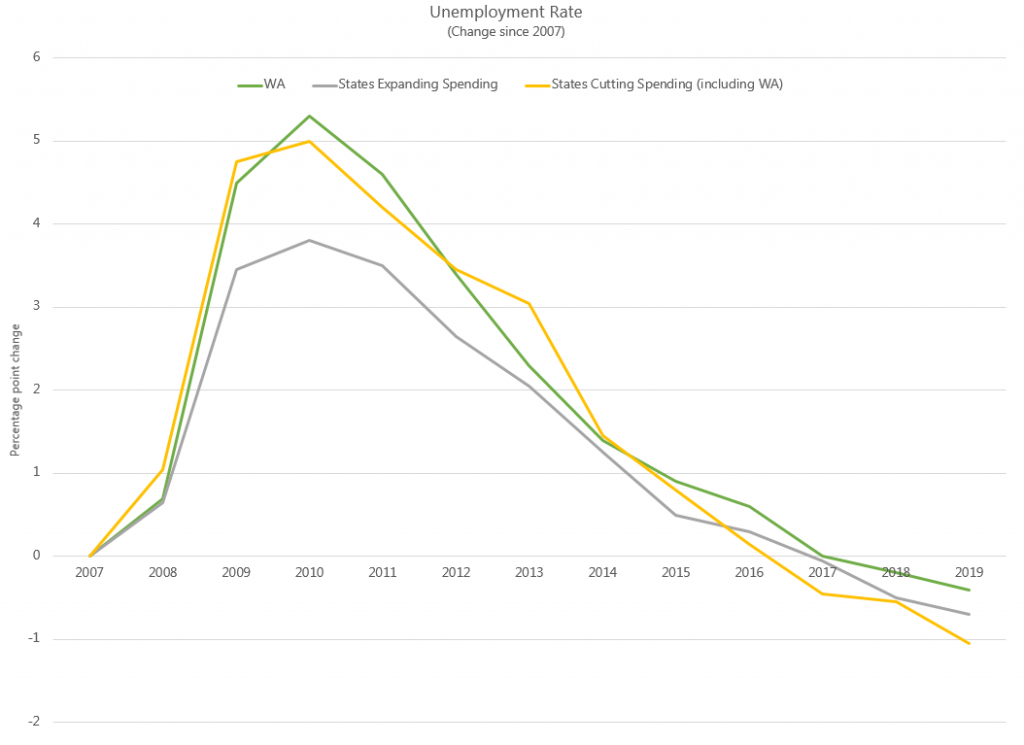

The closest thing to an economic study that I’ve found on the question of how Washington’s budget cuts affected the state economy is this piece from the Center for American Progress in 2012. It simply split the states into two groups: states that cut public spending (including Washington) and states that expanded public spending since the start of the Great Recession. Then it looked at median unemployment rates, private sector job growth, and real GDP growth for each group. It found that the median spending cut state had a higher unemployment rate, fewer private sector jobs, and slower economic growth than the median spending expansion state. From this, it concluded that states “that cut spending have fared worse economically than those that expanded spending.”

However, this exercise doesn’t say anything about Washington in particular. It also doesn’t confirm that it was the spending cuts that caused the lower growth (nor does it address other budget actions that states may have taken at the same time). The states have other differences that could underpin those findings.

The charts below show changes in real GDP, private sector employment, and unemployment rates (like similar charts in the Center for American Progress analysis). I’ve used the same state groupings as the Center for American Progress, but I’ve also shown Washington separately and added data through 2019. As you can see, Washington’s real GDP has grown more since 2007 than either group of states (both through 2011 and through 2019). Washington’s private sector employment didn’t perform as well as the spending expansion states through 2012, but since then it has outperformed either group. Washington’s unemployment rate did increase by more than the median state in the spending expansion group.

Altogether, these data points do not show that Washington’s budgetary response to the Great Recession hurt Washington’s recovery, nor do they show that all-cuts responses in general hurt recoveries. Perhaps Washington’s growth would have been even stronger if a different approach had been taken, but the fact is that we have seen significant growth in GDP and private sector employment. From 2007 to 2019, Washington’s real GDP grew 45.0 percent—the second highest growth in the country. Washington’s growth in private sector employment over the same period grew by 18.4 percent—the sixth highest. Further, this growth yielded extraordinary revenue growth for the state in 2013–15, 2015–17, and 2017–19.

With the September revenue forecast and the October collections report, the state’s budget shortfall is narrowing. If this trend continues, the question of whether to increase taxes or substantially cut spending may be moot.

Categories: Budget , Economy.