8:36 am

February 28, 2022

As the state increased appropriations for schools in response to the McCleary decision on school funding, the share of the budget (in terms of funds subject to the outlook, or NGFO) going to public schools increased from 42.6% in 2009–11 to 51.6% in 2019–21. The share for public schools would drop significantly in the budgets passed by the House and Senate, to 43.1% and 44.2%, respectively.

Appropriations for public schools would be very similar under the operating budgets passed by the Senate and the House. Both would reduce 2021–23 NGFO appropriations for public schools, by $120.6 million in the House budget and by $141.8 million in the Senate budget. That net reduction is due to the substantial estimated savings at the maintenance level (the cost of continuing current services, adjusted for inflation and enrollment). For K–12, the maintenance level is estimated to decrease by $925.8 million, mainly due to lower enrollment in schools.

Counteracting the maintenance level savings, the House budget would increase policy level appropriations by $805.2 million and the Senate budget would increase policy level appropriations by $784.0 million.

The major policy level changes in both budgets are enrollment stabilization, salary inflation, and student support staffing.

Enrollment Stabilization. Last year, the Legislature appropriated $95.9 million for 2019–21 and $27.8 million for 2021–23 for enrollment stabilization.

The House-passed supplemental would appropriate $314.7 million for enrollment stabilization. If a district’s state revenue in SY 2021–22 is less than what the district budgeted for in Dec. 2021, it would receive additional funding (capped by proportional enrollment). Additionally, the funding would cover SHB 1590. Under the bill, local levy limits and local effort assistance for CY 2022 and 2023 would be based on SY 2019–20 enrollment (if greater than enrollment in SY 2020–21 or SY 2021–22).

The Senate would appropriate $346.5 million for SSB 5563 (which has not been passed by the Senate). The bill would provide enrollment stabilization for districts whose SY 2021–22 revenue is less than what it would have been if based on SY 2019–20 enrollment. The stabilization amount would be 50% of the difference in revenue. There would also be stabilization for local levies and local effort assistance.

Inflation. As part of the Legislature’s response to the McCleary decision, it specified that beginning in SY 2018–19, school salaries will be adjusted for inflation annually (RCW 28A.150.410). Inflation for a school year is defined as “the implicit price deflator for that fiscal year” (RCW 28A.400.205). Then, every four years beginning with the 2023 legislative session, the Legislature must review and rebase school salaries: “The legislature shall revise the minimum allocations, regionalization factors, and inflationary measure if necessary to ensure that state basic education allocations continue to provide market-rate salaries” (RCW 28A.150.412).

The enacted 2021–23 biennial budget provides for inflationary increases of 2.0% in SY 2021–22 and 1.6% in SY 2022–23, consistent with inflation as estimated in the Economic and Revenue Forecast Council’s March 2021 economic forecast.

However, the Feb. 2022 forecast of inflation increased to 5.1% for FY 2022 and 2.8% for FY 2023. But at this point, the Legislature can’t change salaries for SY 2021–22 to reflect the higher-than-expected inflation for that year. Under the statute, the Legislature must increase the inflation factor for SY 2022–23 to 2.8%. Then, the Legislature will have an opportunity when they rebase salaries next year to recognize the increased inflation in SY 2021–22 and build that into future salaries. (It goes the other way too: salaries were increased by 2.0% in SY 2019–20, but inflation ended up being just 1.3% that year.)

Instead of waiting for the rebasing exercise, the budgets passed by the House and Senate would increase the inflationary adjustment for SY 2022–23 to 5.5% and 4.7%, respectively. (It’s not clear to me how they arrived at those specific numbers.) This would increase NGFO appropriations by $236.5 million in the House proposal and by $167.6 million in the Senate proposal.

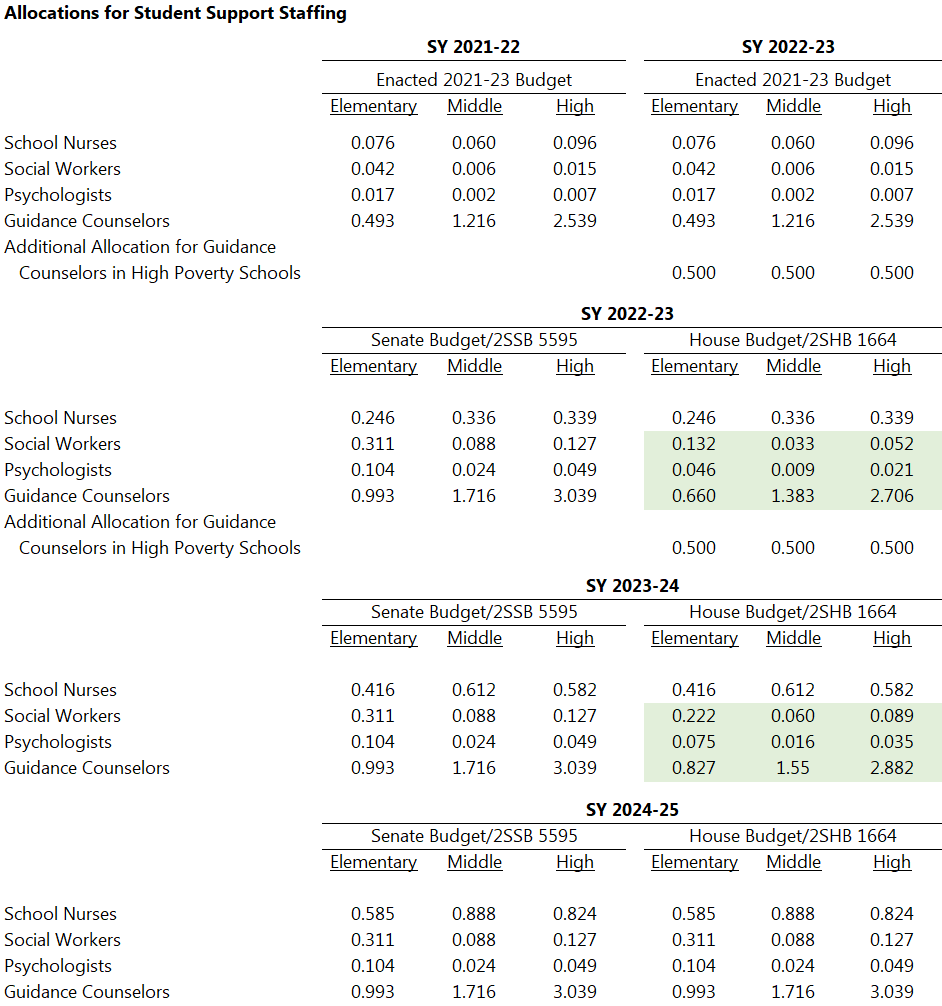

Student Support Staffing. The 2021–23 biennial budget funds allocations for school nurses, social workers, school psychologists, and counselors as shown in the table below. Additionally, it funds an enhancement for guidance counselors at high poverty schools in SY 2022–23.

Both the House and Senate supplemental budgets would significantly increase allocations for these staff members. The House supplemental budget would fund 2SHB 1664 and increase appropriations by $107.9 million. Additionally, the House would keep the SY 2022–23 enhancement for additional counselors in high poverty schools.

The Senate supplemental would fund 2SSB 5595 (which has not been passed by the Senate) and increase appropriations by $173.8 million. The Senate would not fund the guidance counselor enhancement for high poverty schools.

Allocations for these staff members would be the same under both 2SHB 1664 and 2SSB 5595 by SY 2024–25. The allocations for nurses would follow the same phase-in under both bills. However, 2SHB 1664 would also phase in the allocations for social workers, psychologists and guidance counselors. (2SSB 5595 would fund the SY 2024–25 allocations right away in SY 2022–23 for these staff members.)

Other. The House would appropriate $40.4 million for additional allocations for substitutes. The Senate would appropriate $27.4 million to allow districts to use SY 2019–20 free and reduced price lunch percentages when calculating learning assistance program funding. The Senate would appropriate $13.0 million for transitional kindergarten based on projected enrollment increases.

Tags: 2022supp