8:38 am

November 14, 2019

In the wake of the passage of I-976 and the results of some local races, tax policy is an emerging theme. For example, King County Executive Dow Constantine used the occasion to call for comprehensive state tax reform:

Our state’s tax system is inefficient, unfair, volatile, inadequate, and bad for business. Local governments have few tools at their disposal to provide all of the infrastructure and services on which successful communities and a thriving economy depend. Today, our economy is generating unprecedented prosperity, while at the same time governments are forced to cobble together transit and road systems from antiquated, inadequate and unpopular funding sources.

Jim Camden of the Spokesman-Review reports that in response to I-976,

Senate Republicans might push for a change some of their members introduced in the 2019 session. The bill, by Sen. Phil Fortunato, R-Auburn, called for using all the sales taxes collected from the sale of new or used motor vehicles for highway projects rather than sending it to the General Fund with other sales tax revenue. It received a hearing in the Senate Transportation Committee but not a vote that would have sent it to the full Senate.

The fiscal analysis prepared for the bill said it would boost one of the state’s key transportation funds by more than $1 billion per year. But an equal amount would be subtracted from the General Fund, which provides the bulk of money spent on state programs, policies and salaries.

(The bill is SB 5743.)

Kevin Schofield of SCC Insight asked Seattle City Councilmember Sally Bagshaw how the Council would respond to the loss of transportation funds due to I-976. She responded,

Well, there’s one thing that we had raised a couple of years ago, and I think that’s still worth exploring, and that’s the unearned income tax. We think that that can raise a lot of money. My lawyers have told me, “just cool your jets on that, we’ve got to figure out what we’re doing with the income tax as proposed. But I think that this unearned income tax is something that would be perceived as being naturally progressive, that there’s money to be had, it’s constitutional based upon everything that we’ve learned, and I think that’s something that we can go after.

Meanwhile, Daniel Beekman and Jim Brunner of the Seattle Times ask whether the new make-up of the Seattle City Council will mean the return of the head tax. Even if that doesn’t happen, “a new-look business tax and lefty measures in other areas are major possibilities.” Further,

“I look forward to working with the new City Council to urgently pass a strong tax” on companies like the tech and retail giant, [Councilmember Kshama] Sawant said at a news conference Saturday, telling reporters such a tax would help underwrite “a massive expansion of social housing and services.”

She called the election results “as close to a referendum on the Amazon tax as possible,” and also “a mandate for progressive ideas” more broadly, as supporters chanted “rent control, rent control, make Seattle affordable.”

Finally, in a Crosscut piece, contributing columnist Katie Wilson of the Transit Riders Union suggests that I-976 created “a political opening, a chance to rethink how we pay for things.” She notes that Seattle could respond to I-976 by replacing its Transportation Benefit District car tab fees with an increase of the existing 0.1 percent sales tax to 0.2 percent. Additionally, she suggests that Seattle could increase business taxes: a head tax, a payroll tax, a more progressive city business and occupation (B&O) tax, and a tax based on “excessive executive pay.”

In her column, Wilson claims that “Washington is a ‘low tax state’ in terms of revenue collected (hence our trouble funding basic services), but for low-income families it’s the highest-tax state in the country.” These revenue claims originate with a report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP); we wrote about the problems with that report’s methodology here. (Incidentally, one of the problems is that ITEP overestimates the extent to which Washington’s B&O tax is shifted onto lower-income taxpayers—ITEP treats our B&O tax as a sales tax that is borne by consumers. This overstates the regressivity of Washington’s system compared to other states. In ITEP’s analysis, the indirect burden of sales and excise taxes on business that is borne by Washington households in the lowest quintile is higher than the burden of retail sales taxes these households pay directly.)

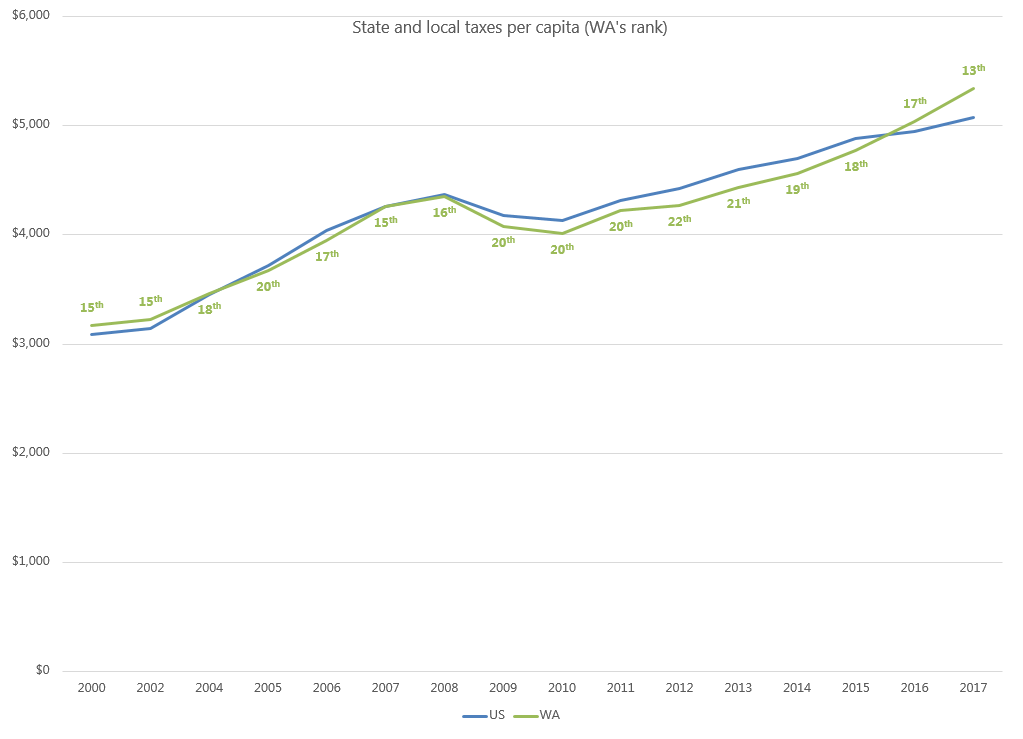

Further, Washington is neither a low-tax nor a low-spending state. In 2017 (the most recent state and local data available), Washington’s state and local taxes per capita were $5,342—13th highest in the country and above the national average of $5,073. Washington’s state and local taxes as a share of personal income were 9.7 percent (up from 9.5 percent in 2016). By this measure, our taxes ranked 30th.

(Moreover, the state has increased taxes significantly in recent years that aren’t yet fully realized in the data, given the lag. For example, the McCleary state property tax and the various tax increases adopted earlier this year aren’t included. For an idea of how things will trend in the coming years: state-only data for 2018 is available from the Census Bureau. This data shows that Washington’s state-only taxes as a share of personal income increased from 28th in the nation in 2017 to 25th in 2018.)

Similarly, Washington’s state and local spending per capita was $10,038 in 2017—14th highest in the country and above the national average. Washington’s state and local spending as a share of personal income was 18.3 percent, 31st highest in the country. And those figures don’t yet include the big increases in spending in 2017–19 and 2019–21 related to the McCleary decision.