7:18 pm

April 18, 2019

The 2019-21 operating budgets passed by the House and the Senate both assume more revenue than is forecasted to be available from current sources. In both cases, budget writers suggest that part of the gap be filled by replacing the current flat rate (1.28 percent) Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) with a graduated rate structure. This would reduce the tax paid on lower valued properties, increase the tax paid on higher valued properties and raise more revenue overall. The existing REET is a volatile tax; a graduated REET would be even more volatile. Because of this volatility, revenue from a graduated REET should be directed to the general fund, where it would be subject to the constitutional provisions requiring three-quarters of extraordinary revenue growth and 1 percent of general state revenues to be deposited in the budget stabilization account.

Under the House graduated REET (contained in HB 2156) the rate would be 0.9 percent if the selling price is less than or equal to $500,000. For properties with selling prices above $500,000 the rate would be 1.28 percent on the portion of the price less than or equal to $1.5 million, 2.0 percent for any portion of the price between $1.5 million and $7 million, and 3.0 percent for any portion greater than $7 million. (Note that there is a discrete jump in the amount of tax owed at $500,000: the tax on a $500,000 sale would be $4,500; the tax on a $500,001 sale would be $6,400.01. The amount of tax is continuous at the other breaks in the rate schedule as the higher rates (2 percent and 3 percent) apply only to portions of the selling price.)

Under the Senate graduated REET (contained in SB 5991) the rate would be 0.75 percent if the selling price is less than $250,000, 1.28 percent if the price is $250,000 or greater but less than $1 million, 2.0 percent if the price is $1 million or greater but less than $5 million; and 2.5 percent if the price is $5 million or greater. (For the Senate graduated REET, the amount of tax owed jumps discretely at every break point in the rate schedule.)

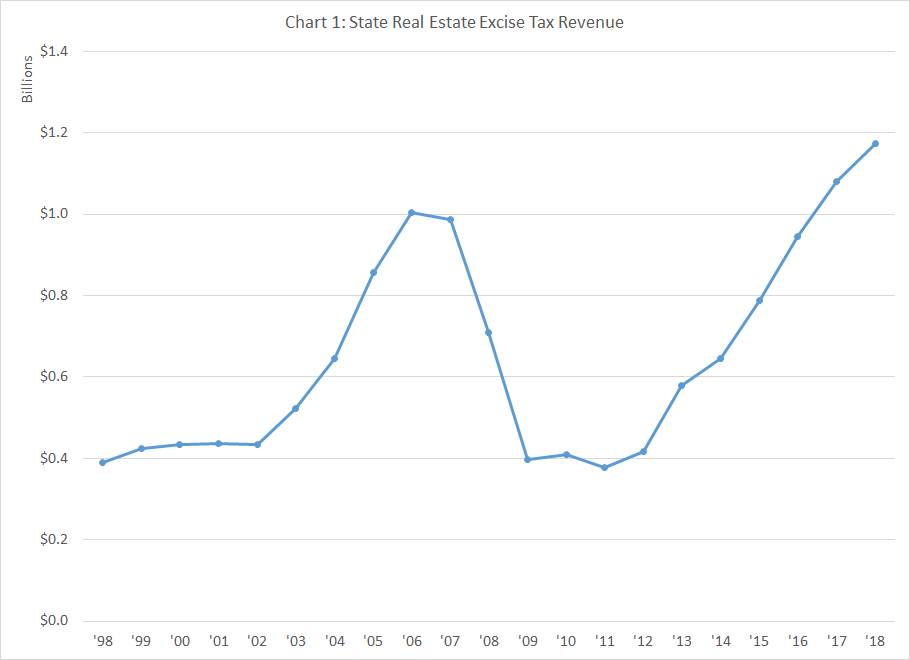

Revenues from the existing REET have swung wildly over the past 20 years, as Chart 1 shows. The drop between FY 2007 and FY 2009, from $986.7 million to $397.6 million, was breathtaking, as was the post 2012 increase.

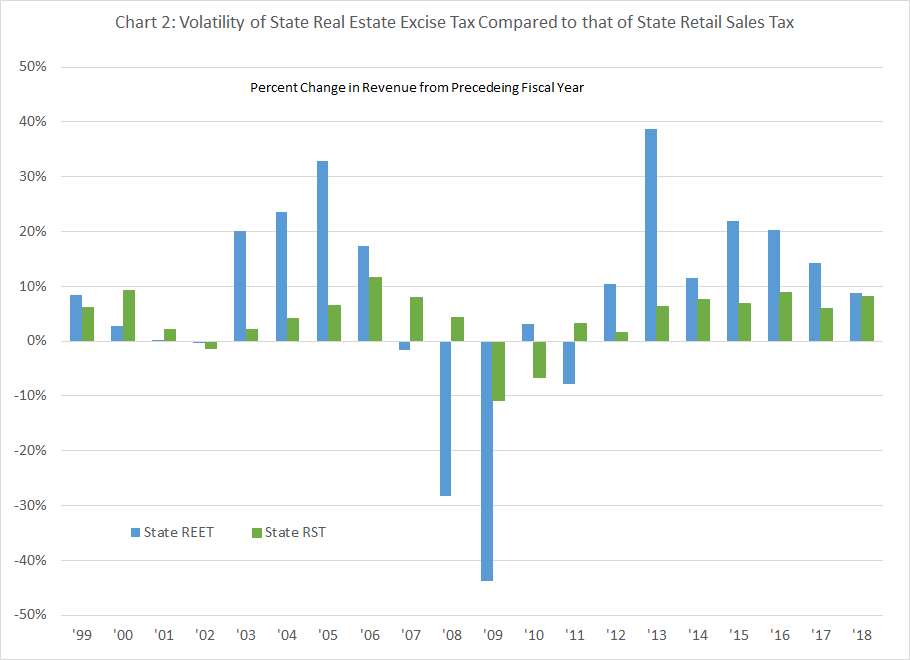

The existing REET is much more volatile than the state retail sales tax (RST) which provides nearly half of state general fund revenues. This is visible in Chart 2, which compares than annual percentage changes in REET and RST over the past 20 years.

One way of quantifying tax volatility is the standard deviation of the percentage change in annual revenue. (See Pew Charitable Trusts’ methodology discussion here.) Over the 1999–2018 period, the standard deviation of the percentage change in REET revenue was 0.186, more than 3 times the 0.053 standard deviation of the RST.

REET’s volatility is particularly troublesome because of the positive correlation between the REET and the RST. This correlation can be seen in Chart 3, which plots the rate of change of REET revenue against the rate of change of RST revenue. The cycle in REET revenue coincides with the cycle in RST revenue for a double whammy on the state budget.

Graduated income taxes are more volatile than flat income taxes. Likewise, a graduated REET would be more volatile than a flat REET. This is because a graduated REET’s average tax rate will tend to increase when the average sale price subject to REET increases and the average tax rate will tend to fall when this average price falls. The negative impact of this increase in volatility will be compounded because the cycle in a graduated REET will coincide with the cycle in RST to an even greater extent than the cycle in a flat REET does.

The state’s primary tool for mitigating tax revenue volatility is the budget stabilization account (BSA, or rainy-day fund) established under Article VII, Section 2 of the state constitution. This provision requires that 1 percent of “general state revenues” be transferred to the BSA each year. Additionally, the provision requires that at the end of each biennium that three-quarters of any “extraordinary revenue growth” be transferred to the BSA. (The constitution defines extraordinary revenue growth to be “the amount by which the growth in general state revenues for that fiscal biennium exceeds by one-third the average biennial percentage growth in general state revenues over the prior five fiscal biennia.”)

Exacerbating the problem of volatility, neither graduated REET proposal fully directs its revenue to the general fund, where it would be counted as general state revenue and thus be subject to the constitutional provisions regarding transfers to the BSA. The House bill directs 55.5 percent of the additional revenue generated by its graduated REET to the Education Legacy Trust Account (ELTA), where it would not count as general state revenue. The Senate bill directs about 90 percent of the additional revenue to ELTA. These proposals would make the state’s general fund less sustainable for the future.

Categories: Budget , Categories , Tax Policy.