1:03 pm

July 12, 2019

Earlier this week, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a study on the impacts of increasing the federal minimum wage to $10, $12, or $15 per hour by 2025. The headline findings are that increasing the federal minimum to $15 would increase wages for 17 million workers, cause 1.3 million workers to lose their jobs, reduce the number of people with incomes below the poverty line by 1.3 million, and reduce total family income in 2025 by $9 billion.

As we have written before, “Increases in the minimum wage are a tradeoff. Some gain, but many lose. Those who keep their jobs and their hours benefit. But those employees who lose their jobs or have their hours reduced lose out.”

CBO does a good job walking through the economics of the issue and appropriately highlights the uncertainty of the literature.

The economic impacts of increasing the minimum would include increasing wages (“though some of those higher earnings would be offset by higher rates of joblessness”), decreasing business income, raising prices, and reducing national output. CBO expects the long-term effects to differ from the short-term effects:

In the short term, raising the minimum wage would increase the economywide demand for goods and services, CBO expects. That is because the families with increased income—who tend to have lower income, on average—tend to boost their spending more than families with decreased income tend to reduce their spending. The increased demand for goods and services, in turn, would raise the nation’s output and income.

In the long term, however, the key determinants of the nation’s output and income are the size and quality of the workforce, the stock of productive capital (such as factories and computers), and the efficiency with which workers and capital produce goods and services (known as total factor productivity). Raising the minimum wage would probably reduce employment, capital, and efficiency, in CBO’s assessment. Over time, those reductions would lower the nation’s output and income.

Further:

Reductions in employment would initially be concentrated at firms where higher prices quickly reduce sales. Over a longer period, however, more firms would replace low-wage workers with higher-wage workers, machines, and other substitutes. Thus, CBO expects that the percentage reduction in employment of low-wage workers would generally rise over time for any given increase in the minimum wage.

On the uncertainty of the estimates, the CBO discusses how it relies on assumptions about wage growth under current law and assumptions about how responsive employment would be to an increase. “If wages grow more slowly than CBO projects, the options would have larger effects on employment than CBO expects.” Also, “there is considerable uncertainty about the responsiveness of employment to an increase in the minimum wage. If employment is more responsive than CBO expects, then increases in the minimum wage would lead to larger declines in employment.”

CBO further argues that “employment is more responsive to relatively large wage increases and increases that will be adjusted for future wage growth.” The paper has a nice chart that shows that the magnitude of a potential increase to $15 nationally would be historically large.

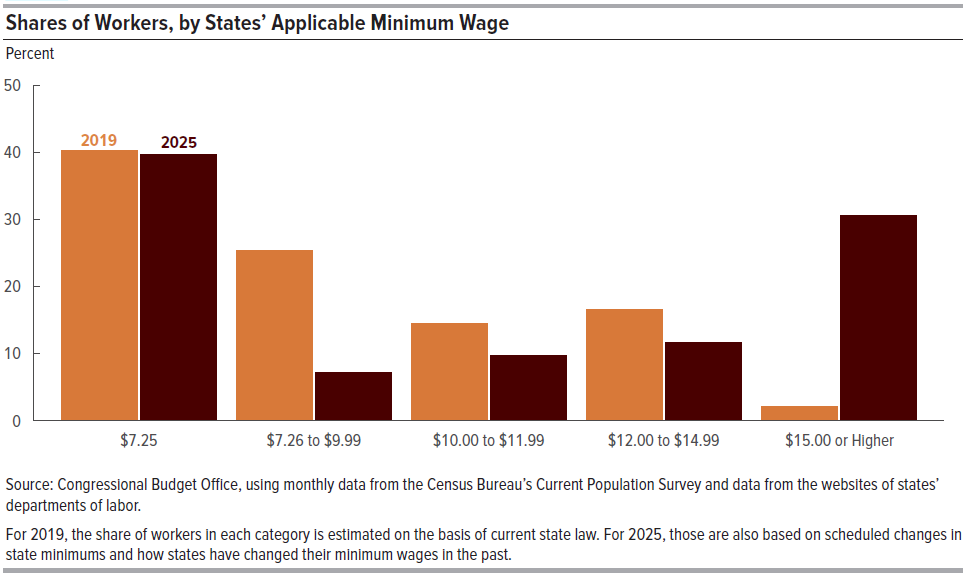

Still, the paper notes that 29 states and DC have minimum wages that are higher than the current federal minimum (these include Washington). CBO estimates, “About 60 percent of all workers currently live in states where the applicable minimum wage is more than $7.25 per hour. And in 2025, about 30 percent of workers will live in states with a minimum wage of $15 or higher, CBO estimates.”

This means that the effects of increasing the minimum wage would differ by state: “states with no state minimum wage in 2025 would see the biggest effects from a higher federal minimum wage. Low-wage workers in those states would see significant increases in their hourly wages and, for that reason, be at greater risk for joblessness.” Washington’s state minimum wage will reach $15 in 2025, based on CBO’s inflation forecast. And in Seattle, many employers are already subject to a $15 minimum wage; beginning in 2021, they will all be.

In estimating the number of workers who would be affected by an increase in the federal minimum wage, CBO accounted for the effects of future increases in state minimum wages, but it “did not account for localities’ minimum wages because the [current population survey] does not identify the localities in which respondents work.” As economist Ernie Tedeschi has pointed out, this means that CBO’s estimates of both the job losses and benefits of increasing the federal minimum are probably too high.

Opportunity Washington also wrote about the report this week.

Meanwhile, economist Jeffrey Clemens has a good piece for the Cato Institute that gives an overview of recent minimum wage research and how it should be read, given that some studies find reductions in employment and some don’t.

He writes that the consensus on minimum wages has been shifting due to incomplete readings of recent research and “shortcomings in the application of economic thinking” (for example, “there is more to a job than its wage” and there is a difference between short-term and long-term responses).

Finally, in discussing the Clemens piece, economist John Cochrane writes about why so much time is spent studying minimum wages. He links to this (rather inside baseball) 2000 paper from Thomas Leonard about the tension between theory and empirical tests on the subject. Leonard notes that “good evidence on minimum-wage effects is hard to obtain” (for example, there are many ways employers can respond to them); “[m]ethodologically, the belief that empirical evidence ‘decides’ when theory applies obviously has less force when the evidence tends to be equivocal.”

Categories: Categories , Employment Policy.